We’re a partnership-oriented team of dedicated professionals on a mission to help businesses in Indonesia grow.

We provide intelligent insights and innovative services and solutions we believe will help you make better business decisions, especially in these times of unprecedented uncertainty.

The Legatum Prosperity Index 2019 for Indonesia is something we want to share with you as it gives an uncluttered perspective on the enormous investment opportunities in one of the world’s most emerging markets.

The following information has been taken from the Legatum Report which you can find by clicking here.

The positive main takeaways from the Legatum Report are:

- Indonesia is politically stable and its democracy is strengthening through greater civil participation

- Indonesia’s economy is growing and more people are experiencing a rise in living conditions

- There are 60 venture capital funds in Indonesia, and the country ranks 25th globally for venture capital availability.

- An improved investment environment has led to the significant development of Indonesian financial markets

- Indonesian governments have improved the country’s investment environment including in the ease of doing business, strengthening competition law, improving patent laws, and implementing stricter laws against copyright infringements

If you find the report useful and you’d like to explore how your business opportunities in Indonesia can grow, we’d love to hear from you.

Prosperity in Indonesia

Prosperity is improving in Indonesia at a faster rate than all but four countries in the world. This success has been built partly on strengthening institutions – particularly social capital – and improving people’s lived experience, but is particularly due to a more open economy.

Though a relatively young democracy, the country is politically stable, more so than many of its neighbours. Five elections have been held since Suharto’s 30-year rule came to an end in 1998, resulting in the peaceful transfer of power, and Indonesia has benefited from a vibrant civil life, which has helped to hold government to account.

The country’s economy and financial sector has been transformed since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. This has led to greater macroeconomic stability yielding greater return for investors, with the burgeoning e-commerce sector a notable success story.

A stable government, regulatory reform, easier access to credit, and an environment conducive to entrepreneurism has led to Indonesia becoming an appealing destination for investment.

With relatively strong institutions and a more open economy, Indonesia’s success is tempered by poor – but improving – living conditions and an education system that, whilst improving, is lacking in the quality of learning required for a growing economy, leading to a projected skills gap in the economy by 2030.

Inclusive Societies: Robust but inexperienced democracy

Since Suharto’s fall in 1998, Indonesia has developed into a robust and stable democracy (the world’s third largest by population).

The country has a high level of political stability, free and fair elections, a constitution that sets out powers for the legislature, judiciary, and executive, and a strong influence of civil society in policymaking.

For such a new democracy, the constraints on the executive power are reasonably robust, and Indonesia ranks 41st in the Executive Constraints element. The main powers are defined in the constitution and a bicameral legislature exists.

This is able to dismiss the President and/or the vice-president if they have violated the law. The President is also limited to two five-year terms.

In the aftermath of the hierarchical, centralised, and authoritarian rule of the Suharto years, governance in Indonesia moved to a decentralised model.

This has caused some obstacles to government effectiveness, such as poor coordination between central and local government. However, Indonesia is ahead of most countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (including China, but behind India), with its rank of 64th for the Government Effectiveness element.

Effectiveness has also been improving, owing to better policy implementation, learning, and co-ordination. A consistent area of success is macroeconomic policy, due to a political consensus around fiscal prudence, which subsequently entrusts technocrats to deliver macroeconomic policies.

Whilst government is reasonably effective and has genuine constraints on its power, corruption is pervasive.

In Malang, East Java, 41 of 45 local city council members were under investigation for political corruption in late 2018.

Vote-buying is common too, with an estimated 25% to 33% of voters receiving bribes for votes. However, there are reasons for optimism, with investigations by a free press and civil society generally allowed and the country rising six ranks in the Government Integrity element over the last 10 years to 81st.

The threat of severe punishments by the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has helped this improvement. Evidence of the KPK’s authority occurred when they sentenced the former House of Representatives speaker and Golkar party chairman Setya Novanto to 15 years in jail for his involvement in a $170 million corruption scandal surrounding procurements for a new identity card system.

Civil society has played its role in making government policy making more transparent.

Vibrant civil society

Much of Indonesia’s success in transitioning to a relatively effective democracy can be attributed to improving levels of civic and social participation, which has helped fuel grassroots participation in politics.

The knowledge gained through civil participation is relevant to the political sphere and has enabled more individuals to enter politics. This has resulted in the strengthening of democracy through Indonesians being able to defend their rights and hold leaders to account.

Indonesia ranks 1st for the Civic & Social Participation element, with the highest levels of volunteering of any country.

The country has a voter turnout of above 70%, the 19th highest of any country, and 29% of respondents voiced their opinion to a public official in the month before being surveyed, the 13th highest proportion in the world.

The public has a strong trust in institutions in Indonesia, with the country ranking 16th for the Institutional Trust element, up 32 places since 2009.

Confidence is highest in local police and national government, at 87% and 84% confidence respectively.

Open Economies: Significant investment potential

Since 1998, successive Indonesian governments have improved the country’s investment environment through instigating a range of regulatory reforms.

These include improvements in the ease of doing business, strengthening competition law, improving patent laws, and implementing stricter laws against copyright infringements.

As a result, Indonesia has risen 24 places in the Investment Environment pillar to 64th in 10 years.

Since 1998, successive Indonesian governments have improved the country’s investment environment through instigating a range of regulatory reforms.

The improved investment environment has led to the significant development of Indonesian financial markets – albeit still relatively small – with the market capitalisation of listed domestic companies increasing from USD 27 billion in 2000 to USD 331 billion in 2018 (adjusted for inflation) and a concurrent increase in the number of listed companies, from 286 in 2000 to 619 in 2018.

The massive potential of the Indonesian market has also attracted large sums of venture capital.

Indonesia is home to four of Southeast Asia’s 10 unicorns (a start-up company valued at over USD 1 billion), all of which are e-commerce ventures.

There are 60 venture capital funds in Indonesia, and the country ranks 25th globally for venture capital availability.

Venture capitalists see major opportunity in the e-commerce market in Indonesia – already the largest in ASEAN – owing to the many problems that start-ups can explore and improve with digital applications, as well as good talent and increasingly favourable regulations for businesses.

GoJek, a ride-sharing company and one of the four unicorns in the country, raised USD 550 million through a venture capital consortium in 2016. The combination of growing financial markets and access to venture capital has caused Indonesia to rise 33 places to 31st in the Financing Ecosystem element over the past decade.

Dynamic economy but hampered by state owned enterprises and the labour market

Indonesia has an increasingly dynamic economy, as evidenced by the flourishing e-commerce market and start-up environment.

Indonesia’s dynamism has been helped by successive governments taking steps to develop a more business-friendly environment.

In 2017, Indonesia established a ministerial, provincial and regional task force to address and improve the inefficiencies that hamper business creation. In Jakarta, for example, in 2004 it took 181 days to start a business at a cost equivalent to 137% of GDP per capita.

By 2019, it took 20 days at a cost of 6.1%. Indonesia now sits at 43rd in the world for the Environment for Business Creation element, up 23 places since 2009.

However, a significant number of sectors are still dominated by a few major players, a hangover from the Suharto years. In particular, State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are still favoured by policymakers and regulators, who are yet to see the full value of effective competition policy.

For instance, about 80% of public construction projects are being handled by SOEs.

The finance sector is also dominated by state-owned banks, leading to the inefficient allocation of resources.

The Commission for Supervision of Business Competition (KPPU) was set up following the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, to supervise the implementation of the Law concerning the Prohibition of Monopolistic Practices and Unfair Business Competition. However, it is relatively weak, has a small budget and only a limited ability to bring cases.

A 2013 OECD survey of 49 countries highlighted that Indonesia was the second weakest in terms of being open to competition.

To encourage competition, the Indonesian parliament recently approved an amendment of the Indonesian Competition Law.

The draft law contains several new features that are designed to empower the competition regulator when handling monopolies and unfair competitions. However, Indonesia’s performance remains just above middling for market contestability, ranking 70th in the world for the Domestic Market Contestability element, down seven places from 10 years ago.

Another challenge for Indonesia is encouraging businesses to enter the formal economy, which will expand the current tax base. Formal employment surpassed informal employment only in 2011.

One of the main restrictions to further growth of formal employment is the country’s restrictive labour laws.

The average cost of redundancy is 57.8 weeks of salary, higher than all but three countries in the world. Indonesian employment contracts are also inflexible with fixed term contracts prohibited for permanent tasks.

Indonesia ranks poorly for the Labour Market Flexibility element, at 119th, which is fourth lowest in the Asia-Pacific region.

Empowered People: Rising living conditions

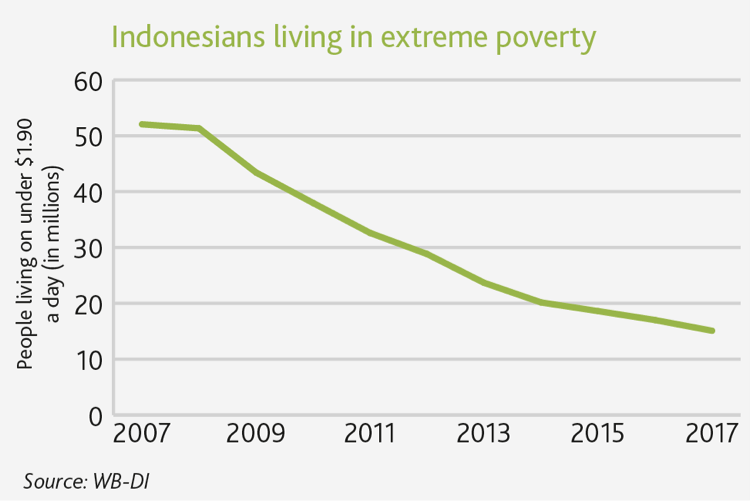

Indonesia has improved the living conditions of many of its people. This has occurred through poverty reduction, the widening of basic service provision, greater connectedness, and a safer living environment. However, the Living Conditions pillar remains Indonesia’s lowest ranking pillar.

More than 35 million Indonesians have been lifted from extreme poverty (those living on an income of less than USD 1.90 a day) since 2007.

Owing to continued economic growth, the country now has over 70 million in the ‘consuming class’ (daily income above USD 10 a day), with this number expected to more than double by 2030.

This rise in income has been accompanied by better access to basic services; 90% are now accessing basic drinking services compared to 81% in 2009, and more than two-thirds of the country has access to basic sanitation, compared to 54% 10 years ago.

A nationwide roll-out of converting kerosene use in homes to gas has resulted in 58% of the population now using clean cooking fuels, compared to 22% a decade ago. There has been a concurrent reduction in life years lost from indoor air pollution of almost a third.

However, the level of nutrition across the country has not improved significantly over the past decade and in the past couple of years there has been an increase in the proportion of children in this bracket (although the level is lower than a decade ago), with Indonesia among the weakest performing 15 countries.

There has also been a rise in the proportion of the population with insufficient resources to pay for adequate food, up from 22% in 2009 to 41% currently.

Education faltering; a skills gap is looming

Whilst improvement has been seen in completion rates at all levels of education and enrolment rates at all levels except primary, the quality of learning has not improved and there remains a significant learning gap at the tertiary level, leading to a skills gap in the labour market.

With unemployment rates among the highest for most recent graduates, the quality of learning at both the secondary and tertiary level is low.

Indonesia ranked in the bottom 10 countries in each of the most recent reading, maths, and science PISA assessments, with a declining score in both educational quality measures.

Indonesia has nine universities in the top 1,000, but none in the top 250. Seven are public universities, which are competitive and only have capacity for less than 20% of Indonesia’s graduating secondary students.

To cope with rising demand (enrollment rates are up to 36% from 20% in 2009), there has been a growing number of smaller, private providers.

It has been estimated that by 2030 Indonesia will have a shortage of 3.8 million workers with post-secondary education. There will be a shortage of 7.5 million workers with upper secondary education and a 6.7 million shortage of lower skilled workers.

Conclusion

Indonesia’s success, as the fifth most improved country overall over the past decade, has arisen out of a stabilised political foundation, a reasonably robust democratic society, and the influence of an active civil society.

The environment for financial investment and business creation has significantly improved, leading to a more open economy.

However, a more competitive market is required to create an even more open economy.

While social capital is strong in Indonesia, rooting out corruption will lead to more effective institutions. The lived experiences of millions of Indonesians have been improved through reductions in poverty and increased access to education, but more needs to be done to improve the quality of education and address the projected shortfall in skilled workers to meet the increased demands of the growing economy

If you’ve found this report useful and would like to explore your business opportunities in Indonesia with us, we’d love to hear from you.